A Zulu Healing in South Africa

By Judith Fein

My husband Paul, who is quite a skeptic, nonetheless had a healing experience with a dead person — actually multiple dead people, which began when our plane was about to land in South Africa. He started experiencing extreme pain in his ear. Even after we landed, his ear still hurt, and finally we went to a doctor who said his eardrum had almost burst, and he wouldn’t be able to take a flight home.

So we extended our trip in South Africa, and Paul took the antibiotics and steroids that were prescribed, but the pain in his ear persisted. It didn’t stop us from delighting in the deep culture and people of South Africa, but it was distressing to see how uncomfortable Paul was.

Finally we decided that we had to go in another direction, both metaphorically and literally. With a Zulu-speaking guide, we went to Kwazulu-Natal to find a sangoma, or native healer. She trained the other sangomas in the area, and locals raved about her powers.

We entered a hut where she was performing a ceremony, surrounded by drummers and attended by acolytes. She didn’t look at Paul, but she picked up a mortar and pestle, mixed some herbs, and drank them. Immediately her voice became deep and otherworldly. In a jerky movement, she lifted her hand to her head and cupped it around her ear. Then she looked straight at Paul and spoke. Our Zulu interpreter translated what she said. “You think your problem is your ear, but your problem is that you don’t know how to connect to your ancestors. You must perform a ceremony and invite them into your life.”

Then she gestured for Paul to come forward and stand next to her. She took a red yarn-like thread and wrapped it around his torso, draping it over his shoulder and tying it. She told him he had to wear it for several months, as I recall.

Paul, who is not woo-woo and doesn’t indulge in magical thinking, grew very silent as the sangoma told him exactly, precisely, how to make a ceremony to invite the ancestors in. It involved colored candles, the gate of our house, and speaking their names.

Paul spoke in a low voice to the healer. “I don’t know anything about my ancestors –– not even their names,” he confided.

“It does not matter,” she said, slowly and clearly. “But you must call them in.”

She said he could do it in South Africa, and then when he got home. He nodded his agreement.

Paul kept the red string on at all times, except when he showered. And he planned his ceremony. He invited a few men to be part of it, and he performed it at the gate of the hotel where we were staying. He became a bit emotional when he called out to his deceased ancestors, asking them to come to him, and to help him. He said he realized what a loss it had been to grow up with no connection to his forebears; it had been discouraged in his family.

“I felt, for the first time, that they were not just grandparents and great grandparents and great-great grandparents; they were also people who were once young, and had hopes, dreams, aspirations, joys, and sadness. They had loved and lived, and then they had passed on, and no one spoke their names or remembered them,” he told me. “I thanked them all, even though I don’t know their names. It didn’t seem to matter. I just thanked them.”

After the ceremony, Paul went to sleep. When he woke up, his ear was healed.

When Paul told his doctor about what had happened, the latter said there was a much more rational explanation: the ear infection took longer than expected to heal. Sometimes that happens. The medication doesn’t work at first, but it facilitates healing over time. It wasn’t the sangoma, the ancestors, or the ceremony that healed Paul. And he added that healers can be dangerous, and ancestors are nice, but they don’t affect healing.

Rational explanation. I wanted to open my mouth and say what I was thinking, but I refrained. What was the use? The doctor was trained, he had experience, and he was just giving Paul his best shot at a logical explanation. He was a kind man who meant well. But to me, his thinking was very limited and limiting.

What I wanted to but didn’t say was that the rational brain is necessary and very useful for many things in life, and none of us would be happy if we couldn’t think, but I have come to believe that sometimes thinking can also be a reflection of mental imbalance. We go over and over what-ifs in our minds. We think with regret and anger about the past and create fearful scenarios about the future. We think about all the mistakes we have made and how incompetent we are. We think we are inferior or superior to other people. We think about how others think of us, and that we have nothing important to say. We think that people who annoy us are doing it on purpose. We think that we have to behave, act, dress, and talk in a way that conforms to the expectations of others. We worry, fret, anticipate, and dwell on things that are harmful to our wellbeing. Thinking about solving a mathematical problem, studying and learning any discipline, fixing something in the house or car that is broken, the meaning of a poem, how to help someone, why the sky is blue, a funny joke, choosing a good restaurant for dinner, the book we are reading or film we are watching, planning a party, going on vacation, calling a friend, what to say on a job application are good uses of the brain.

But there are ways of thinking that lock us in, prevent us from being open to new experiences, make us disbelieve things that are not explainable through reason, lead us to scorn or reject things that are mystical, supranatural, or defy rational explanation. And when this happens, we are the losers. We cut ourselves off from wonder, mystery, and deep experiences that can transform our lives. We have nothing to lose by asking “what if?” rather than slamming the door in the face of the non-rational with a resounding no. No, it’s not possible. No, it’s not real. No, it’s not for me.

Paul, who is an inspired, creative, and very rational being, who has no interest in organized religion or organized spirituality, who doesn’t go out looking for experiences or people that are mystical, who distrusts anything that he deems “misty moisty,” nonetheless accepted an offer from a Zulu healer to reach across time to ancestors he hardly knew, communicated with dead people, and was healed. And recently he agreed, when prompted during a talk about death and dying, to write a letter to those grandparents he never really knew. I didn’t read the letter, I don’t know its contents, but I knew from the deep exhale he emitted after writing it and the smile on his face moments later, that he felt satisfied, perhaps relieved, and connected.

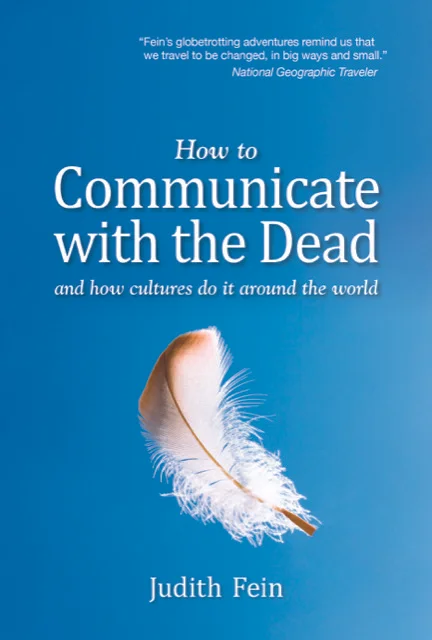

This article is an excerpt from the new book, HOW TO COMMUNICATE WITH THE DEAD…and How Cultures Do It Around the World, by YourLifeisaTrip.com executive editor Judith Fein. She spent 20 years, as an international travel journalist, experiencing the way other cultures look at the continuum of life and death.