Dead Men Talking

By Maureen Magee

Last spring, three young men - ancestors of mine - drifted into my head and took up residence, insisting that I pay attention to them. They nudged other thoughts out of the way, inhibited my ability to work, and even halted my house work. I would find myself, dust-cloth in hand, staring into space, wondering about three uncles whom I had never met. There was much to wonder about, but little to know. My only family-related facts were that Allan and John had died in World War I and Bob had returned home with shell shock. But “the boys” (as I started to think of them) lodged in my mind - vaporous as ghosts - and refused to leave. And so, because I am a writer, I wrote a letter to them, asking what they wanted of me. My tentative guess was that they wished me to write about them - a book, a story? I suggested that, as there were few facts available, it would have to be fiction and that was definitely not my expertise. Having never communed with ghosts before, I was unsure how long (or in what form) an answer would take. After a few days with no hints from the boys, I assumed that meant, “Go ahead, give it a try.”

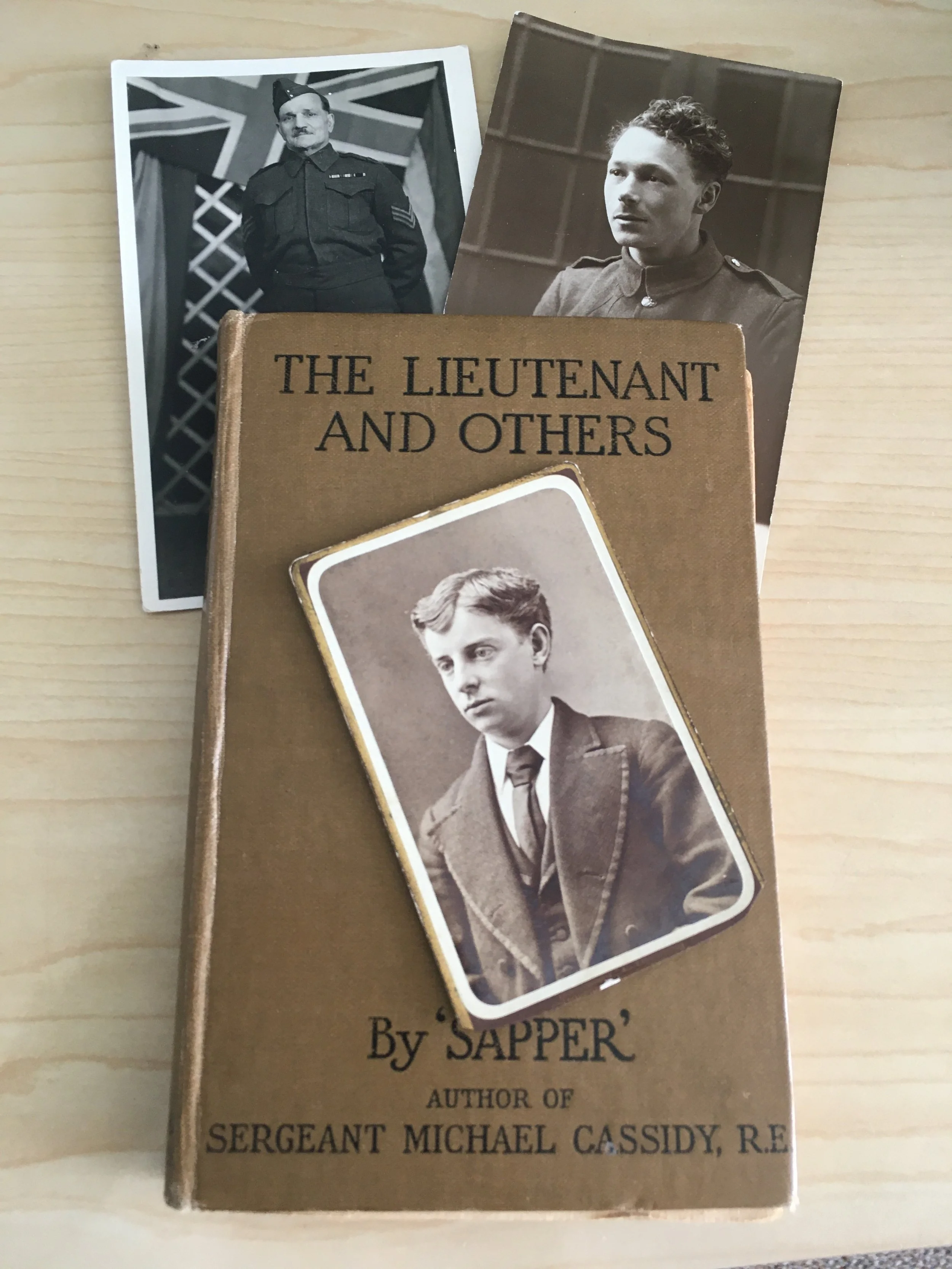

And so off I went, to spend months reading about the war, from 1917 tomes written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (fiercely patriotic, but not factually reliable) to the delightful Sapper-authored stories written by a soldier in the trenches. Grinding my way through analyses of various generals’ military plans, I spent days with a map tracking the boys’ battles in France (such a tiny area for such a disastrous war.)

But the most important research were the letters, stories and books written by the soldiers themselves, where I learned of the military planning ineptitude, the lack of awareness that this was a far different war than any that had been fought before. Battlefields didn’t move more than a few yards for months at a time; men slept, ate and defecated in mudholes for one or two weeks before being replaced. Soldiers could not determine which was worse, the days and nights of ferocious shelling, or the unearthly quiet as they waited for it to start again. Not enough food was planned, shoes fell apart in the mud and guns were selected that jammed with fast firings.

I learned, over and over, what “the fog of war” meant.

Through the Canadian War Museum records, I compiled a spread sheet tracking each uncle’s history of when he enlisted, which ship he travelled on, and what their conditions were (some luxurious, others barely survivable.) I could follow my uncles as they were transferred, injured, had leave or went AWOL. Uncle John had been transferred to his brother Allan’s unit, but Allan was killed just before John arrived. I learned that fifteen-year-old Uncle Bob had been in his British training camp only two weeks when it was bombed. Although he never “saw action” or received a physical injury, he came home unable to cope with life.

I tracked down relatives I’d never met, searched online, in libraries and bookstores to try and find “my story.” In a war memorabilia shop I combed through sepia photographs and found three portraits that seemed perfect for each of my faceless uncles. And then, I began to give them qualities - shyness, bravado, ineptitude, strength, nerves. Each fact I found was followed by questions. Fact: Allan died shortly after entering battle. Questions: was he, as the oldest, a leader amongst the brothers? Or was he a bit inept, couldn’t manage a gun, which is why he died early? Fact: John was in action the longest time - so he may have been stronger. Question: or was he just lucky? He died three months before the armistice and that made his death seem more tragic. I wanted to glorify them, because of what they had suffered. But the need to “invent” them to weave them into a fiction made me uncomfortable. Dishonest, even. What if one or the other were not nice guys at all? Perhaps one had a mean streak or was lazy? Did they enlist out of loyalty? Or did they merely hope to escape poverty and get two meals a day? No one knew; and I balked at what I perceived as a potential betrayal of them.

It was easier to keep at the gruesome research, and I fell back into it with enthusiasm - an odd word, but even though I hated what I read, I could not stop reading. The boys hovered in my mind throughout, but they were not nudging at me, like they had before I started the project. I felt confident that, if I required feedback, they would give it to me, and they did. After several months of watching me wallow in the trenches with them, they just . . . drifted away. Poof, gone. And left me wondering, “What the hell had all that been about?”

It seems to me now that they didn’t need the fabrication of a story at all and I cringe, looking back on my idea. It feels shoddy, as if it was more about me, than about them. Now, I believe they just needed someone to know. They wanted someone to care enough to learn more and to empathize.

I don’t have much in the way of religious beliefs, but I do like to think of reincarnation and I hope that each of my uncles has found or will some day find a way to return and have a chance to experience a different kind of life. I like to wonder if - at some point - I may have encountered one of “the boys” in their new persona, and whether perhaps, we shared a look, or a brief smile, as we passed by each other. Who knows?

Maureen Magee is a Literary Associate at Helping You Get Published. She has a BFA, has taught Travel Writing courses and been published in several periodicals and newspapers. Her memoir Jumping the Bull: Surviving Life, Love and Adventure in Ethiopia is on Amazon. Maureen’s original letter to her uncles was published by YourLifeIsATrip.com as A Letter to the Missing.