Discover the Exotic on a Road Trip

“None of your business,” she said. The short, curly, white hair bounced as she shook her head, but the brown eyes smiled in her beautiful, tanned and weathered face. Half Navajo, Suzie (not her real name) has lived in Rio Grande pueblos in New Mexico all her life. We were sitting in a rambling adobe house near the village where she lives with her husband. Grandchildren and daughters dropped in from time to time as we talked. The smell of cedarwood smoke curled around us, and tin-framed pictures of saints glinted on the walls.

“We travel to find new ways of seeing the world,” I said. “Although all humans deal with some basic questions, various cultures find different answers. How do we show respect to others? Where did we come from? Who created us? How do we ensure good fortune, food, and shelter? What do we need to know? The more the answers differ from our own, the more exotic the culture seems.”

The curt reply, “None of your business,” came from Suzie, a lively Pueblo elder who fervently believes in the Catholic religion, but just as devotedly follows ancient ways. People come to her for counsel and healing. Although Suzie inherited an outgoing personality and sense of humor from her Navajo mother, she got her sense of propriety from living in her father's Pueblo culture for all of her 80 years.

I visited Suzie's husband Joe (not his real name) while writing a book about Navajo artist, Quincy Tahoma. Finding this couple turned out to be a grand slam for a biographer. Tahoma, a little older than Joe, had been a mentor to Joe when they both attended Santa Fe Indian School. Joe's father gained fame as one of the first Pueblo painters to sell his work, and, now in his eighties, Joe has returned to painting that he had abandoned after his school days.

Tahoma visited Joe's family often as a student and also as an adult. As a bonus, I learned that Suzie's brother had been one of Tahoma's best friends, so he spent a lot of time with her family as well. “He liked talking Navajo with my mother,” Suzie says.

During that first visit, I clicked on the tape recorder, pulled out my notebook, and ran down the long list of questions my co-author and I had been wondering about. Because neither of us is Navajo, we wanted to ensure that we captured the artist's cultural background correctly, and Suzie and Joe could fill in the gaps in my understanding.

Did he truly not know his clan as he claimed, and what would that mean to a Navajo? Suzie and Joe said it would leave a huge gap in his life if he did not know.

Was he a Catholic? And if not, why is he buried in a Catholic cemetery? The couple had never known him to go to church.

People have told us that Tahoma carried a Navajo medicine pouch. What would have been in it?

“None of your business.”

“But,” I persisted, “I have read anthropological reports that talk about medicine pouches.”

“Don't believe those. When those guys come around we just tell them whatever we feel like telling them, and they think they have the truth.”

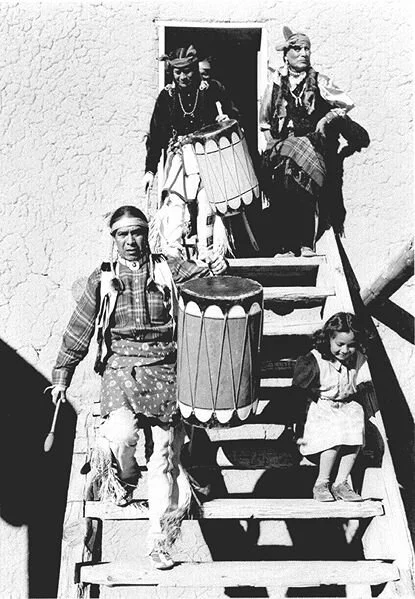

Over the months and years of visiting New Mexico, I became friends with the couple and went back several times. Joe invited me to come to Pueblo's feast day in January. Age-old ceremonial dances started in the frosty dawn and visitors appreciated a chance to warm up in one of the cozy homes around the central plaza. Every family had set up a long table and served a meal that lasted all day. It was like the biggest church potluck you can imagine.

Because I had learned on that first visit that in the Pueblo culture one does not ask questions about religious matters, I stifled my curiosity about the dancers who streamed in and out of underground kivas all day. Teachers, bus drivers, potters, and ranchers arrived at the Pueblo and transformed themselves into ancestors or animals. After their dance, they set aside their deer masks or buffalo horns to tuck into jello salad or pork and posole, once more ordinary members of the community.

Children of the pueblo do not ask questions. They get explanations when adults deem they are ready. In this area, I was still considered a child.

However, on my next visit to my friend Joe, he brought up the subject of the dances and told me a bit about his responsibilities and how he was passing the leadership on to a nephew. I guess that in his eyes, I was ready to learn.

One chilly feast day, I was sitting on the porch with Joe and we chatted in between the greetings from other visitors. By their deferential attitude toward Joe, I realized that he was not just another guy in Pueblo. He was an important elder. The realization that I was privileged to have him as a friend in more ways than just my own research, crowned what had been an exhilarating day. Bright blue skies, wood smoke from fireplaces in all the homes around the plaza, good home-cooked food, families gathered in reunion, and amazing, beautiful ancient dances.

Joe and I stood on the porch and, as I said goodbye, I impulsively hugged him. But he stood impassive and solid. Suzie laughed and I suddenly remembered. Pueblo people do not hug. Although the Navajo (Diné) people I had met were quick to express their affection with a hug or pat on the shoulder, the Puebloans, with their reserved dignity, rarely touch someone outside the family.

Suzie looked on with an amused grin at Joe's reaction. Joe is firmly grounded in his own culture, but because he lived and worked outside the Pueblo for many years, he is tolerant of the ways of other cultures. Therefore, my gaffe was not fatal to our friendship. However, we were in a Pueblo village, surrounded by other people. It must have been disconcerting for Joe, to say the least.

I treasure the opportunities I have had to learn more about the Pueblo and Navajo cultures. These people who speak different languages, and view the world so differently than I do, seem exotic. But to visit and learn from them, you do not have to take a trans-oceanic flight or cross international boundaries. Just come to the Southwest and drive through New Mexico and Arizona. The exotic can be close to home.

Vera Marie Badertscher and her co-author Charnell Havens wrote Quincy Tahoma: The Life and Legacy of a Navajo Artist, which will be published in the spring of 2011. Vera Marie also blogs about books and movies that inspire travel at A Traveler's Library.

Photo file from the Wikimedia Commons.