The Risks of Time Travel in Santa Fe

by Elyn Aviva

We punched in the entry code on the keypad on the side of the looming concrete storage building, opened the door, and walked down the empty, darkened corridors to our numbered unit. We unlocked the roll-up metal door and pushed it up, revealing a colorful hodgepodge of items stacked along the walls and piled on metal shelving units in the center. We were entering a mysterious domain, a mixture of refuse dump and Treasure Island.

This was the stuff we had left behind six years ago in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when my husband, Gary, and I moved to Spain. Now that were happily settled as expats in Girona, Catalonia, Spain, the time had come to clear out the storage unit. No more excuses.

Carefully, we stepped over rolled-up Chinese carpets we no longer needed, squeezed between carefully labeled cartons of clothing that no longer fit, boxes of books we no longer wanted to read, containers of yellowing hand-embroidered linen bed sheets and table cloths, and plastic storage bins filled with “bits and bobs” of fabric, beads, and buttons. We puzzled over items that seemed of little value but took up lots of space. Why had we saved that, we asked each other, or that? Or that?

I wondered: Who am I without these things, these carefully guarded objets d’art that say (or at least I thought they said) “something” about my aesthetic sensibilities, my travel experiences, my status in the world? Who am I without my Nambe flatware, Sasaki dishes, few high-end bits of crystal, rare Japanese inlaid screen, treasured antique Chinese cloisonné vases inherited from my mother, unique hand-crafted ceramic bowls—Turkish silk rugs, framed art photos and original prints, my favorite this and that, my seemingly irreplaceable knickknacks?

These things, these possessions, were stored in our storage unit—but the reverse was also true: the possessions stored our memories. Memories of a trip to Istanbul, a visit to a Native American pueblo, a pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago in Spain, an outing to a Santa Fe craft show. Memories of myself, memories of my family. The framed portraits in oil of me at age three and my long-dead brother, Tommy, at age five. My first “official” work of art and my first free-hand embroidery. Drafts of poetry I had published when I was at university; drafts of short stories that never saw print. It was like traveling back in time.

Suddenly the enormity of what we were about to do hit me. How could we get rid of things that had become memories? Without them, would I still remember who I was? What I had done? Where I had been? Gary saw the panic in my eyes and held my hand.

We worked our way to the back of the storage unit. Here were the intimidating stacks of file boxes that included not only our shared history but also “The Feinberg Family” archives. When my father died, I had inherited it all, but I had been in too much grief to explore the contents, to sort through the accumulated record of my parents’ lives. It had felt like digging through their graves.

So I had put it all away, out of sight though never really out of mind, in the back corner of a temperature-controlled storage unit in Santa Fe, New Mexico, waiting for a better time to sort and toss. There never is a good time, I realized, but there’s also never a better time than right now. And besides—that’s what we had come to do.

We planned a strategy. Ask our respective kids if they wanted any of it (short answer: no). Haul the rest of it over to the consignment shop located at the other end of the storage building. Take the boxes of financial and personal records to our rented condo and sort. I would send important historical documents to the Special Collections archives at the university where my parents had been professors.

I dreaded the process, as if I knew that going through these file boxes would be like walking through a field laced with buried landmines of memory. But I persevered, traveling back in time, sifting through plastic bins of photos without labels and boxes of letters sent by people I had never met. I found a tarnished framed wedding photo of Mom and Dad, taken in Chicago in 1938. They smiled at the camera with innocent trust and mutual love. I glanced at carousel trays filled with slides of exotic locales visited by my parents during their wide-ranging travels. To my surprise, I discovered a set of leather-bound journals my father had started writing when he was 12 years old, the contents now blurred and illegible.

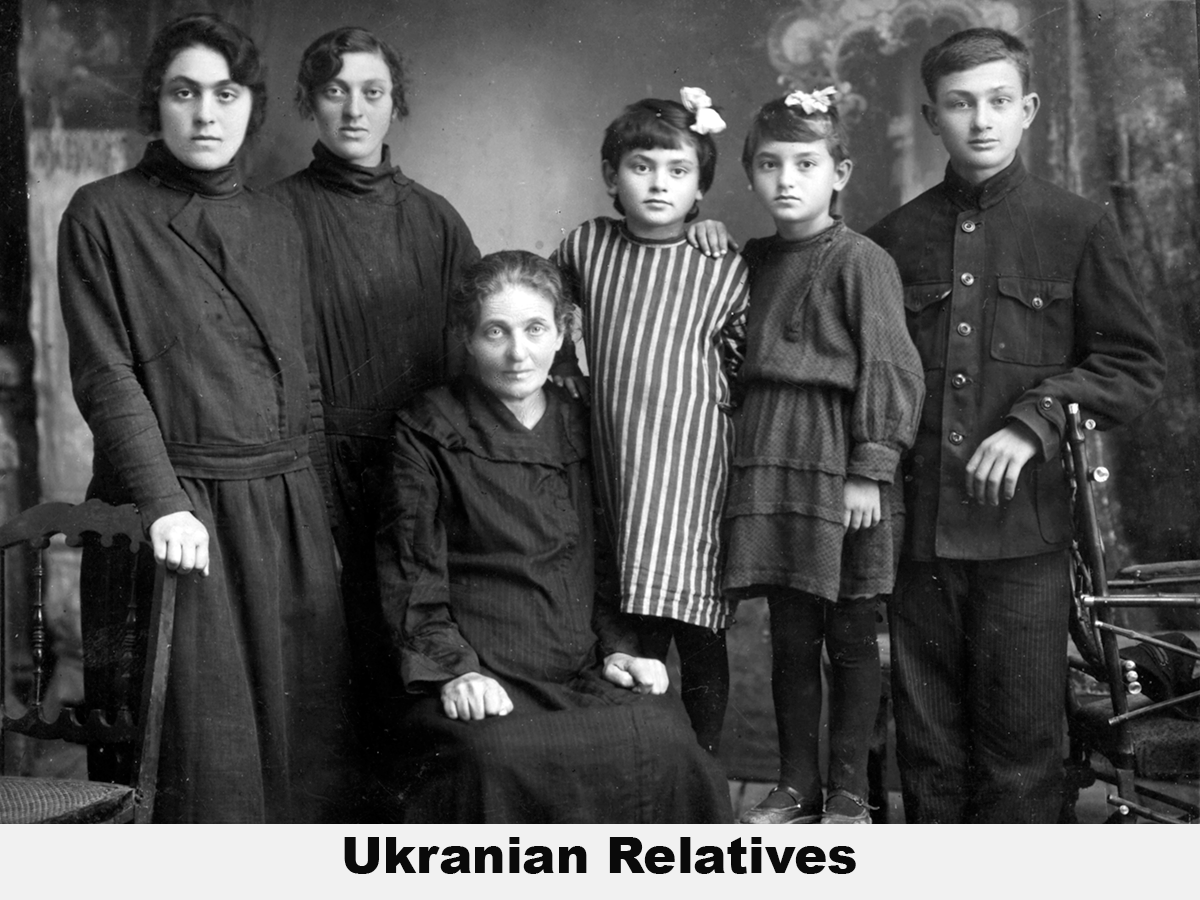

I turned the stiff black pages of ancestral photo albums, smiling at the baby photo of my father taken in Vitebsk, Belarus, in 1914, shortly after he was born and nine years before he and his mother fled the Communist Revolution and came to Chicago, Illinois, leaving his father behind. He had been jailed by the Bolsheviks and died in prison. I mused at the photos of my mother’s parents taken in Odessa, Ukraine, before they fled the pogroms and the Czar in 1910. They also ended up in Chicago. My ancestors had traveled far, but not because they wanted to.

In another album, I found a cute photo of Tommy and me in a little red wagon. Mom had labeled it “June 1950.” He was five, I was three. On the back, Mom had written, “Tommy, after recovering from polio.” Tommy after recovering from polio? What about me? I had had polio too—we had been hospitalized together—and I was in the red wagon, squeezed in behind Tommy. But it was as if I didn’t exist. I turned to Gary tearfully. “Well, there you have it. The story of my childhood, encapsulated in a photo caption.” Gary tried to comfort me. “She must have labeled the photo after Tommy died, lost in grief ….” I considered the possibility. Then I shook my head. “Good try, but no. Tommy didn’t die until a year later.”

I stuck the albums in a box to send to my son, knowing that he would probably put it in the back corner of his garage, waiting for a better time to sort and toss.

And then I opened an unlabeled box and took out a manila folder, and grief exploded like a bombshell. It was palpable, a grey miasma that filled the room and dimmed the daylight. “Tommy Feinberg” was the label on the file, written in my father’s careful handwriting. My brother. Killed in a truck-bicycle accident in August 1951, when he was almost seven and I was almost five. More than 60 years ago—but how long ago is that? Judging from the power of the grief, no longer ago than yesterday.

Apprehensively, I looked inside the dog-eared manila folders that I hadn’t known existed. Police reports. Witness accounts. Hospital reports. The bill for Tommy’s hospital stay. Obituaries. His birth certificate, complete with his tiny inked footprints. The text of his memorial service. Sobbing, I read them one by one, my tears staining the slightly rumpled pages. Going through this material was, indeed, like digging in a grave.

The story of the fatal accident that I remembered being told didn’t quite match what the reports revealed. Close, but not quite. Were my memories wrong, or had the story been distorted by my parents’ anguish? The trouble with this kind of time travel is, there was no one left alive to ask. Confusion filled the room, along with grief.

Hands shaking, I took the folders and stuffed them back in the box, then taped it shut. I’d had enough of time travel.

But what to do with it? We couldn’t place the box on a funeral pyre; we couldn’t toss it in the trash. Gary put it in the back seat of the rental car and drove off to UPS. We sent it to be buried in the university archives. May it rest in peace.

How ironic, I thought. I had worried that by “getting rid of stuff” I would get rid of all my memories. Now, I wished it were that simple.

Elyn Aviva is a transformational traveler, writer, and fiber artist who lives in Girona, Spain. Her blog is www.powerfulplaces.com/blog. She is co-author with her husband, Gary White, of “Powerful Places Guidebooks.” To learn more about her publications, go to www.powerfulplaces.com and www.pilgrimsprocess.com. To learn about Elyn’s fiber art, go to www.fiberalchemy.com. Gary’s blog about their expat life is www.fandangolife.com.