When Keturah Kendrick returned to visit East Africa, she had a craving for goat brochettes at Le Poete. When she lived as an expat in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, she’d been within walking distance of the restaurant and gorged herself on skewers of grilled goat several times a week. On this visit, however, satisfying the craving proved to be an adventure of its own.

All in Culinary Travel

Traveling In A Garden

No one knows when we’ll be traveling again. So for now, while we’re still staying close to home, lifelong gardener BJ Stolbov provides his suggestions for growing a vegetable garden, an exciting adventure right in your own yard.

Food Sharing, Barcelona Style

Some people love to share their food. Kristine Mietzner, not so much. Then a Barcelona food tour changed everything.

Shanghai Hairy Crabs

Erin Mooz flew halfway across the world to visit her college roommate’s hometown, Shanghai, during Hairy Crab season, one of the city’s most anticipated culinary events of the year, and discovered there was more to the tradition than the delicious crustaceans.

A Foodie's Iran: 2 Authentic Recipes You Can Make Right Now

by Paul Ross

Warned not to go, I followed my appetite to Iran and have returned home filled with beautiful memories, blessed with new friends, and brimming with the desire to show and tell, taste and smell, and surprise all those who never expected to see me again.

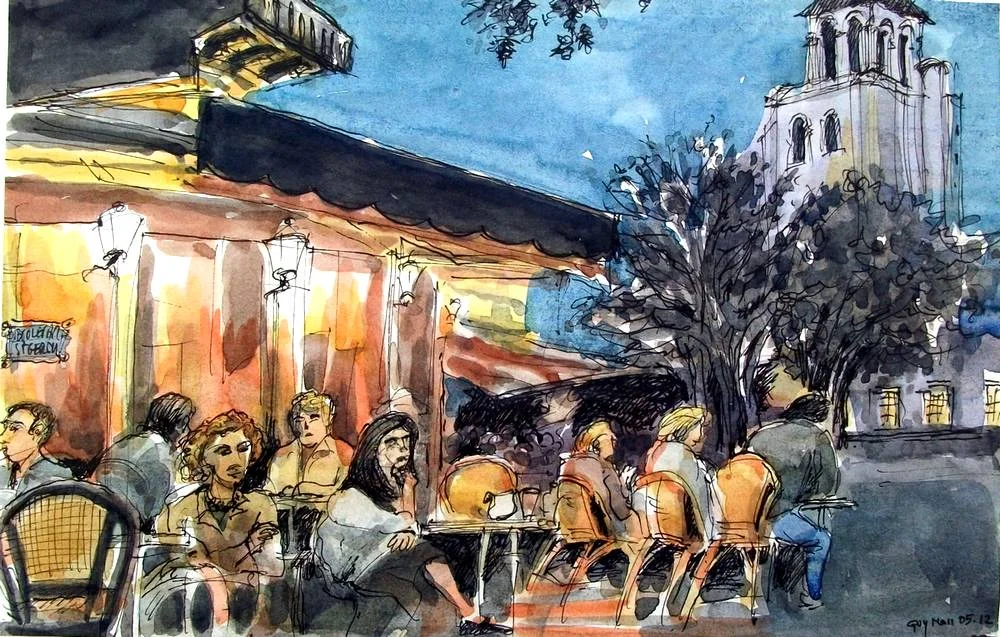

Mastering the Art of French Dining

by Dorty Nowak After growing up in a family where dinner was eaten off trays in front of the TV, I wanted to create a gracious dining atmosphere in my own home. Lit candles and cloth napkins were the norm, and I combed Good Housekeeping for tips to better the ambience for my family and guests. However, it wasn’t until I moved to Paris that I discovered how little I knew about what truly makes a pleasurable dining experience.

by Dina Lyuber

My husband Roman and I were both born in the former Soviet Union. I moved to Canada when I was still in diapers; he spent his childhood in Leningrad before moving to the States. Neither of us had been back since, but after we’d met and married, we decided to go back to the USSR (as the song goes) – though the Soviet Union no longer existed, and neither did Leningrad. We were returning to St. Petersburg in Russia, and name changes aside, that meant a return to our roots, our long-ago home.

My in-laws still had contacts in the country, and we were offered free accommodation in a private medical clinic just off of the Fontanka Canal, across from the Summer Garden and minutes away from the bustling Nevsky Prospect. The clinic was housed in a Baroque-style building decorated with reliefs and statues of winged angels. Inside, the corridor was dim and narrow, permeated by a medicinal smell. A large kindly woman showed us to the spare room in the basement. There was a modest bathroom in the hallway. The water running from the taps had a brownish tint. There was a fold-out couch to sleep on and a good-sized kitchen. It wasn’t a bad space, but it was cold. It was August, and I was freezing.

We spent the first days of our two-week trip rambling through the city. We never took taxis or buses, but padded down the wet sidewalks and absorbed the fresh-air smell wafting from the Neva river.

A Partner Post by PerpetualExplorer.com contributor, Emma Corcoran.

Two or three times a week, Jay Savsani hosts a meal on the rooftop of his Chicago apartment complex. Last week his dinner guests were two Swiss tourists, and this week he’ll be hosting some fellow Chicagoans. Jay and his fellow diners are strangers but have connected through MealSharing.com, the food-centered social networking site Jay founded last year.

MealSharing allows diners and hosts from around the world to meet and share a home-cooked meal. Hosts put a profile on the site, which lists the types of food they usually cook and displays photos of their past culinary creations. Guests can then make contact and request a meal. MealSharing is a free platform; it costs nothing to participate as a guest or a host in this “couchsurfing for foodies” social movement.

“We come from a mission where we care about bringing communities together; be it from an international standpoint or within the local area,” says Jay, who says that “MealSharing is platform that connects travelers; however people also use it as a way to eat with other meal-sharers in their hometown.”

by B.J. Stolbov

It was a dark and cool morning. I was up before dawn. Quietly, I put on my boots and my hat. Then, accompanied by my protective guard dogs, Julius and Brutus, and my intrepid, knife-wielding guide, Samuel, we started out into the jungle in search of the elusive wild banana blossom.

The hills rolled away like brown buffaloes. Sighing as if still asleep, the trees drooped in the morning stillness. Birds flittered from tree to tree. Except for the sound of the distant chickens, a sound as pervasive as breathing itself, it was unusually quiet. The morning was calm. Not a breath of air moved. The dew was still thick on the tall grass. My view, from close to far, was green, jungle green, dark green, light green, middle green, green and green, everything was green. And I was searching for anything that wasn’t green. I was looking for yellow bananas and below that the most colorful plant in the jungle, the rare wild banana blossom. A banana blossom is a beautiful specimen. It is a deep reddish-purple and shaped like a huge upside-down rosebud.

Bananas, in the wild, come in many varieties, shapes, sizes, and colors. The Saba is a thick banana. It is much like the plantain in the supermarket that everyone looks at but no one seems to know what to do with. The Saba is used for boiling into soups and stews, or just boiled, peeled, and eaten cold much like a potato. It is also boiled in sugar water to make a delicious dessert called banana glaze. It can also be deep-fried and rolled in sugar to make banana-que. Lakatan and Latundans are both sweet, eating banana, with the Lakatan being the sweetest-tasting banana I have ever eaten, especially when it is freshly picked. Empress bananas are the tiniest bananas, about the size of the palm of your hand and can be eaten in about two or three tasty bites. The long, yellow, perfect banana that you see in the supermarket is called a Cavendish. It is probably originally from near here. But your perfect banana, domesticated and grown on enormous plantations throughout the tropics, is no longer a wild banana.

The Quest for La Baguette

Ahh, la baguette, quintessentially French. Biting into your favourite baguette is a soothing affair that will bring a smile of contentment to your face. When you find a good one, all others pale in comparison. Every time my feet land on French soil, I start anticipating my first tasty baguette that will welcome me back to my second home. But it has to be the right baguette. Just as not all French wine is worth drinking, not all baguettes are worth consuming.

Crusty on the outside and hole-y on the inside, the perfect baguette is not too chewy, but rather soft with small bits of bread that ball up in your mouth as you chew. It can be slightly tangy and definitely has a distinct aroma. And baguettes are serious business in France with the average person consuming half a loaf per day. Precise laws protect this French institution with strict regulations concerning the ingredients; any kind of additives are an absolute faux pas. Flour, yeast, water and salt are all that is needed. A light dusting of flour on the outside, and 20 minutes later, voilà, your baguette is ready to devour.

As serious baguette lovers, I knew my daughters and I would have our work cut out for us when we moved to Paris. With over 1800 boulangeries in the capital and 12 within a 10-minute walking distance of our new apartment, some taste-testing would definitely be involved. As soon as we dropped our suitcases in our new Parisian flat, we happily took on this challenge. I felt like Goldilocks of the three bears fame—I knew it would take several attempts until we got it "just right."

I am sure you’ve heard that Spanish food is incredible, that it’s unlike anything you’ve ever tasted, that it’s innovative and bright and well, you know – all that hype. Here’s the thing. It’s totally true. Unfortunately, it took me a good two years of living in Spain to realize it.

Let me back up a bit. I moved to Spain on the premise of staying for nine months – just enough time to explore Europe and sink my teeth into Spain before heading back home. My first day in Spain, I was all alone. I hadn’t made friends yet, but that clearly had no effect on my hunger, and I walked into a little bar to order a sandwich. Now a sandwich in the United States is a hefty sort of thing, layered with ingredients and toppings and sauces. And as I was fairly hungry when I ordered this “sandwich,” I was more than disappointed when two flimsy toasted pieces of sandwich bread came my way with a little lettuce, tomato and a fried egg stuffed between them.

Okay, so my first experience wasn’t great, but over time I did learn to enjoy Spanish food. I liked it. I really liked it. But I never reached the point of loving it. I continued ordering the same things again and again at restaurants and bars, and never felt it was special. In my head, American food was superior to the simple and often bland food of Spain.

About a year and a half after I moved to Spain, I met my Spanish boyfriend, and I decided to tell him my opinion about all of this. He was shocked. I thought he was too proud to admit I was right, but I realize now I was horribly mistaken. As we continued dating, I started tasting foods I had never even heard of before, and I had to come to terms with the fact that after eighteen months of eating three meals a day, I actually knew nothing about Spanish food. Actually, my realization was an epiphany.

The dog's tail wagged impatiently. Lady -- a small, nondescript, white and brown mutt -- raced ahead to the oak tree, sprinted back and forth, nose thrust into the ground, then triumphantly started digging with gusto. Looking up with an air of satisfaction, Lady was handsomely rewarded before her master carefully scraped the loosened dirt with his pick. The five visitors observing the ritual looked on expectantly. Using his fingers to gingerly explore further, the truffle hunter delicately removed his treasure: a large, walnut-size white truffle, one of the epicurean riches of Alba, a gem of a city in the Piedmont region of northwest Italy.

Okay, let me just say that up to now the closest I had come to a truffle was in a Whitman’s Sampler box and it was covered with chocolate. And I’m pretty sure it had never been routed out by a dog. This truffle hunting is a respected art form in Alba, and proper training of the dogs is at its heart. Any breed can aspire to the job, but selection depends upon its resume. It must have a good nose (a trait the dogs presumably share with the region's prestigious wines), and trainers can ascertain that after three days. Once the dogs show promise, they attend the Barot University of Truffle Hunting Dogs, in operation since 1880, for two to three months of specialized training. Graduate school is optional.

Now let's talk truffles. Sure, to the uninitiated, it may just be a foul fungus, but to the gourmand, it represents the ultimate in gastronomic delights. It is judged by size, color, shape, texture, aroma - some would say offensive olfactory onslaught; others, fragrance of the gods -- and its overall perfection. There's a lot to be said for this smelly little mushroom.

story + photos by Michael Housewright

Brunello di Montalcino is perhaps the finest wine produced in Italy. It is made entirely from Sangiovese grapes, grown just outside the hilltop town of Montalcino, in Tuscany. It was the first wine I ever loved.

I met Mario Bollag at a wine bar I curated in Houston, Texas. He spoke impeccable English, and was easily the most charming winemaker I had met in all my years in the business. In addition, he made outstanding Brunello at his winery, Terrlasole. We hit it off immediately, talked, and tasted wine for several hours. He invited me to visit him and the winery as soon as I could make my way overseas.

Less than two months after Mario’s visit to Houston, I took him up on his offer, and went to Italy. With my wife in tow, and a rental Volkswagen Golf procured, we set out from Rome airport in search of Mario Bollag. Being a frequent traveler to Italy I assumed finding Mario in tiny Montalcino would be a cakewalk. I was wrong.

Adventures of a Cookbook Traveler

by Dorty Nowak

I collect cookbooks the way others collect travel books. More than souvenirs of places I have been, they help me recreate memories and whet my appetite for further trips. Over the years, I’ve accumulated an impressive library, with Europe, Asia and the Americas grouped together on my bookshelf. When I open Provence, the Beautiful Cookbook, and look at a picture of glossy tomatoes clustered with deep green zucchinis, papery garlic, and branches of rosemary I can taste the wonderful ratatouille I had in Nice, and I’m there once again.

I developed a taste for culinary travel early. My mother, who hated to cook, had a limited repertoire, which reflected her German-Irish roots. Meat, potatoes and vegetables cooked to a uniform grey were standard fare and I could usually predict what we would have for dinner by the day of the week. The Joy of Cooking was the mainstay of her library. It was, and is, a no-nonsense compendium of recipes, with no pictures to grace its pages. When I was fortunate to travel to Europe in college, the pleasure of sampling new foods and the beautifully illustrated cookbooks I collected were almost as exciting as touring the sights.

Use It Or Lose It: A Japanese Tea Story

Thirty years ago, I was dazzled by my action-packed month visiting a friend and his family in Japan. They live in Fukui Prefecture near the Sea of Japan, but I gazed in wonder at the Gion Festival and temples in Kyoto, kabuki theater in Tokyo, the deer park in Nara and Himeji castle from Shogun days. The most delicate and intimate thing I recall was a tea ceremony performed by a friend of my friend at her home.

Relais San MaurizioAlright, we all know by now that drinking red wine is supposed to be heart-healthy. So then, shouldn’t slathering a glass of Merlot on your body be good for the skin? Such is the theory, sort of, at the Caudalie Spas. There are currently only four in the world, and I am luxuriating in a ‘vinotherapie’ massage in the Relais San Maurizio Hotel in the heart of the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy. The vintage is being absorbed into the skin rather than ingested into the bloodstream.

Relais San MaurizioAlright, we all know by now that drinking red wine is supposed to be heart-healthy. So then, shouldn’t slathering a glass of Merlot on your body be good for the skin? Such is the theory, sort of, at the Caudalie Spas. There are currently only four in the world, and I am luxuriating in a ‘vinotherapie’ massage in the Relais San Maurizio Hotel in the heart of the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy. The vintage is being absorbed into the skin rather than ingested into the bloodstream.

As is also true in Bordeaux, France, Rioja, Spain and New York City (Hmmm; don’t exactly think of the latter as a major wine-producing area…), here wine is king! And the appreciation of its many attributes – which, as those who know me can attest, I try to experience as often as I can – is a venerated practice. So it seems appropriate that the consumption of wine extend beyond traditional imbibing.

by Elyn Aviva

When we went for an early morning stroll in Girona, Catalonia, my husband, Gary, and I saw a group of well-dressed people standing impatiently outside a shop. We took a closer look and saw a storefront with impressive, fluted grey stone columns, large display windows, and imposing glass double doors. The merchandise on display was unusual: small metallic capsules in coordinated colors arranged in geometric designs. Emblazoned in glowing white letters over the doors was “Nespresso.” Nespresso? The coffee capsule brand?

When we went for an early morning stroll in Girona, Catalonia, my husband, Gary, and I saw a group of well-dressed people standing impatiently outside a shop. We took a closer look and saw a storefront with impressive, fluted grey stone columns, large display windows, and imposing glass double doors. The merchandise on display was unusual: small metallic capsules in coordinated colors arranged in geometric designs. Emblazoned in glowing white letters over the doors was “Nespresso.” Nespresso? The coffee capsule brand?

The crowd grew increasingly noisy and impatient. We decided it was time to leave before they became even more restive.

I was puzzled. Who would want to purchase pre-made coffee capsules? It seemed neither cost-efficient nor ecologically sound. And besides, when you ran out, there was nothing you could do—except wait desperately for the Nespresso shop to open.

Returning from our stroll, we paused again at the shop. Nespresso was its name and luxury was its selling point. From our vantage point we could see inside. Slim young women in classy matte-black uniforms stood near the open door, gatekeepers into this exclusive club. People entered, sometimes showed a membership card, chatted for a moment discreetly, and then were ushered into this high temple of gustatory excess.

by Elizabeth Weinstein

“If I have to hear one more time about that roast chicken your father had in Tuscany....” my husband says, shaking his head. He feigns disgust, but in truth my husband is amused at the way my family compares every meal we eat to some better meal we had once upon a time. And the best of those meals were always in Italy. The ‘roast chicken in Tuscany’ has become our tagline for the holy grail—the holy food grail.

My parents lived in Italy a generation ago and, culinarily speaking, came of age there. During our growing-up, my brother and I were lucky enough to spend a year and several seasons in that country of hot, meaty broths that simultaneously console and inspire; fresh spinach with warm, oily garlic; pan-fried steaks bright with lemon and salt; and tortellini alla panna that could make you cry.

But it is indeed the roast chicken that does a Marcel Proust number on me—or rather would, if only I could have a bite of that chicken I ate 45 years ago at a restaurant called Cecco’s in Pescia. Just tonight if I could have a taste of pollo al mattone, a fresh chicken flattened whole between two bricks and roasted crisp and succulent on a spit with—with what seasonings? Was it really only salt?—then I would remember what it was like to be five years old and travelling with my parents and my big brother from Lucca back to our temporary home in Florence. I would be able to feel again the warmth of being safe with my family and at home in a foreign country.

by Elyn Aviva

When we told an English friend that we were going to Wales for a few weeks, he looked at us with undisguised pity.

“Bring your own food,” he urged.

“Bring your own food,” he urged.

“Surely you’re joking!” I replied with a laugh.

He shook his head grimly. “Trust me. Bring your own food.”

I have celiac disease, and finding gluten-free (GF) restaurant food can be a challenge—even in countries renowned for their cuisine. I must stay away from wheat, barley, rye, kamut, and spelt in all forms, including bread and flour. What travails would await me in Wales, I could only imagine.

Filled with foreboding, my husband, Gary, and I headed off to Wales to do research for our “Powerful Places Guidebooks” series. Late at night we arrived in Cardiff, capital of Wales, and headed to our B&B. Actually, it was a “B” with only one “B”: bed. Our host offered us an alternative to a homemade breakfast: discount coupons for breakfast at the hotel across the street.

The next morning, we strolled over to the hotel’s unprepossessing side entrance, pushed the door open, and walked on faded carpet to the shabby dining room. Plates displaying the gritty remains of congealed eggs, burnt toast, and greasy bacon were piled on the tables. Hesitantly, we approached the barren breakfast buffet. The plastic cereal bins were nearly empty, and the bowl of fruit salad held nothing but a few wrinkled orange slices stuck to the bottom. Apparently, we had missed the early morning breakfast rush. Judging by the unappetizing remains, it was just as well. We began to worry. Maybe our friend had been correct about Welsh food.

by Eric Lucas

Hardly anything seems secret about a kernel of blue corn. It’s the size and shape of a baby’s tooth, the indigo color of ocean dusk, not rock-hard but sturdy, like old pine.

Such a seed would be a secret, were it a product of American industrial agriculture—patented, engineered at a molecular level, sold under some trade name like Blue 7X-RR. You would pay a large Midwestern company to have some; you’d use huge machines like science fiction robots to lay it in the ground; pour on it chemicals with carbon-chain formulas as long as Finnish words; autoclave it into foods as artificial as plastic. And you’d get your pants sued off if you attempted to replicate it or reproduce it in any way.

Photo by Manya Kaczkowski, 2010But the handful of blue corn seeds I’m holding represent a gift from, first of all, Robert Mirabal, a Taos Pueblo resident; also a gift from two millennia and the ground on which a billion people live. Corn is the bedrock of civilization in the Western Hemisphere. It built a dozen empires in Mexico and South America; helped create two dozen thriving cities in the desert Southwest about which Spanish explorers marveled so much that their colonizer, Don Juan de Oñate, declared his conquest a “kingdom.” Nuevo Mexico; it’s called New Mexico now, but still part of the kingdom of corn. And the seeds Mirabal has given me are no secret, just gifts from that kingdom’s treasure.

Photo by Manya Kaczkowski, 2010But the handful of blue corn seeds I’m holding represent a gift from, first of all, Robert Mirabal, a Taos Pueblo resident; also a gift from two millennia and the ground on which a billion people live. Corn is the bedrock of civilization in the Western Hemisphere. It built a dozen empires in Mexico and South America; helped create two dozen thriving cities in the desert Southwest about which Spanish explorers marveled so much that their colonizer, Don Juan de Oñate, declared his conquest a “kingdom.” Nuevo Mexico; it’s called New Mexico now, but still part of the kingdom of corn. And the seeds Mirabal has given me are no secret, just gifts from that kingdom’s treasure.