Misled on St Michael’s Way, Cornwall

by Elyn Aviva

It took nearly 11 years and three attempts for my husband, Gary, and me to complete the 12-mile-long St Michael’s Way across the southern tip of Cornwall. That’s a rather long time for a short walk—probably a record of some sort. And even though we ended up hiking more than 12 miles, we never did manage to walk the middle five.

But we persevered, although we were misled every step of the way.

In September 2004 we were visiting St Ives, on the southwest tip of Cornwall, when I read a brochure about St Michael’s Way. This coast-to-coast footpath begins near St Ives and is the only trail in Britain that is part of a designated European Cultural Route—the Pilgrim Route to Santiago in Spain.

For decades, I have been drawn to pilgrimage roads—to going on long walks that explore the landscape of the soul as well as the contours of the land. To journeys that get the body in motion and the mind in repose. To walks through rural countryside, punctuated by sacred sites, that lead to an obvious external goal and a to-be-discovered internal destination. My first pilgrimage had been on the Camino de Santiago in Spain in 1982—so of course I was hooked, line and sinker, by the idea of walking the route beginning in Cornwall.

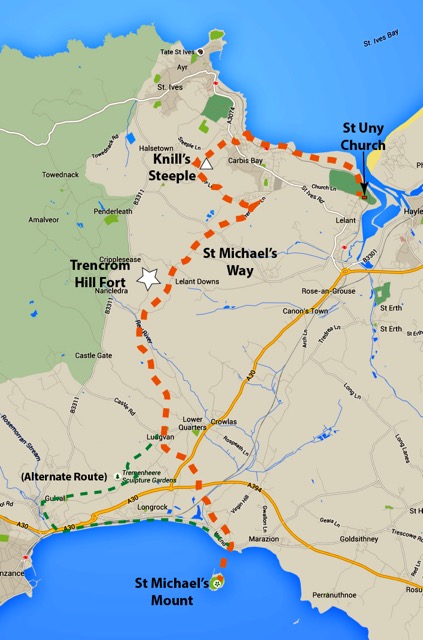

St Michael’s Way was officially waymarked in 2004, but it has a long history. According to the brochure, medieval pilgrims, early Christian missionaries, and travelers followed the route, especially if they came by boat from Ireland or Wales. Rather than sail through the treacherous waters off Land’s End, they disembarked near St Ives and walked approximately 12 miles south to the tidal island known as St Michael’s Mount. St Michael’s Mount was an important medieval pilgrimage destination—not as important as Santiago in Spain, but clearly worth a visit.

I knew for sure that this was our kind of pilgrimage—only 12-ish miles long, waymarked, undoubtedly punctuated by medieval sacred sites and powerful places. An easily do-able journey we could complete in a day. Going for a long walk didn’t interest me, but following in the footsteps of nameless, numerous pilgrims did.

So on a chilly, blustery, rain-spattering Sunday, Gary and I took a taxi south from St. Ives, past Carbis Bay, to Lelant, where St Michael’s Way begins. We began our walk with a brief visit to Lelant’s St Uny church, a heavily restored 13th-century church picturesquely located on a sandy headland overlooking the bay and next to a golf course.

We were a bit puzzled. The waymarked trail led north from Lelant back to Carbis Bay, then turned south. We wondered what self-respecting medieval (or modern) pilgrim would walk north just to turn around and walk south? Surely, we told each other, some legitimate, historical explanation would be revealed as we journeyed on. After all, this was an authentic medieval—or even older—pilgrimage route, wasn’t it?

We struggled against the heavy, wind-blown rain that pelted us as we crossed the golf course (a sign warned us to beware of flying golf balls) and continued along the coast. After reaching Carbis Bay, we turned south, heading to Knill’s Steeple, a very tall, 18th-century granite pyramid that contains a small, empty burial chamber in its base. How strange, we thought, that a medieval pilgrimage trail would lead us to an 18th-century edifice.

We got lost trying to find our way out of the yellow gorse and broom that surrounded the monument. Eventually we used our hiking sticks to bushwhack our way through the dense, prickly vegetation and back to St Michael’s Way. Soon the not-so-well waymarked trail led us toward Trencrom Hill, a Neolithic hill fort. What was that doing on St Michael’s Way, we wondered?

We began to seriously question the historical accuracy of this so-called pilgrims’ way. We began to suspect that it was a marketing scheme to take walkers to local sites of (dis)interest or to pleasant scenic vistas. Medieval pilgrims took detours, but they did so to visit sacred sites of power, not to pay homage to a dead St Ives’ Customs collector—and certainly not to visit an unexcavated, 5500-year-old hillfort. I re-read the brochure. Next on the route was a visit to the front garden of a former Wesleyan (Methodist) chapel, now a private home. We looked at each other in disbelief. This was a medieval pilgrimage route? Not likely!

We were cold, soaked, and weary. We hadn’t wanted to go for a walk, we had wanted to go on a pilgrimage. Clearly, we were misled as well as lost. Disillusioned and disgruntled, we decided to head back to our hotel in St Ives. This was easier said than done, however, since we didn’t know how to get back.

So we staggered on until we reached a country pub. We pushed open the door and were inundated with noises, smells, and bright lights. We had stumbled into the British institution called the Sunday Carvery, where long buffet tables are laden with haunches of overcooked meat and bowls of gravy, and large, overfed people sit in front of heaping plates of meat, potatoes, tasteless veggies, and peculiar desserts with names like Sticky Toffee Pudding, Spotted Dick, and Eton Mess.

Cringing from the din, I asked a waiter if he could call us a taxi. He gestured toward the cashier, and after a pleasant, though very loud, exchange, we waited, chilled and dripping, on a bench by the door until the taxi arrived.

Thus ended our first attempt to walk St Michael’s Way.

Our second attempt, in June 2014, was even less successful, although the weather was much better. This time we were based in Penzance, a few miles from St Michael’s Mount and the southern end of St Michael’s Way. We were traveling with a small group of people and a leader. Walking St Michael’s Way was first up on the itinerary. In the spirit of communal adventure, Gary and I put aside our doubts about the route and, again, we were transported to Lelant. Again, we started walking north. This time, however, our intrepid leader took us on a detour down to the beach. In order to rejoin the Way, we had to wade through knee-high water and scramble up dangerously slippery rocks on the side of a steep cliff. Again, we got lost.

This time we decided to quit sooner rather than later. So when we reached Carbis Bay, we waved goodbye to our companions and waited patiently for the next train back to Penzance.

Thus ended our second attempt to walk St. Michael’s Way.

In July 2015 we were back in southwest Cornwall. As we walked up the tree-lined trail to the Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, we passed a narrow wooden bridge. Painted on the side was the stylized scallop-shell symbol of the Pilgrimage Route to Santiago and the words, “St Michael’s Way.” An arrow pointed toward a footpath.

I turned to Gary with a grin. “Shall we give it one more try?” He grinned back. “Of course.” After all, St Michael’s Mount wasn’t far away, just a few miles to the southeast—if we didn’t get lost, that is. In our previous attempts, we had had expectations—that we were on an authentic medieval pilgrimage road, that it would be well marked, etc. This time, we had no expectations.

After visiting the sculpture gardens (worth a pilgrimage of their own), we walked across the footbridge. Following the waymarked trail, we climbed over moss-covered stone stiles and hiked northeast across the fields into Ludgvan. There we stopped to explore the 14th-century church, founded on a 7th-century Christian sacred site. Suddenly I realized: we were on the real pilgrimage route, the authentic St Michael’s Way, at last! I felt giddy.

As we left the church, we met two friendly ladies. They assured us they often walked through the woods on St Michael’s Way, and they pointed to a wooden trail sign. Without a second thought (or second glance), we set off through the woods, down the hillside, and up a narrow trail covered with densely intertwining tree branches.

A chance sighting through our verdant tunnel revealed that rather than walking south toward the coast, we were walking north. Somehow, we had gotten lost. Again.

Eventually our trail crossed a country lane. We asked directions from a woman walking by, and she pointed back the way we had come. “No way,” I said. We would not retrace our steps. Walking in circles was one thing; walking backwards was quite another. So she described a route that would take us south and would, eventually, intersect with St Michael’s Way.

An hour later we were strolling on a raised wooden footpath through the lush Marazion Marsh, getting closer to St Michael’s Mount with every step. The tide was out, so we were able to walk across the exposed causeway onto the island.

It had taken us 11 years, but we had at last reached the Mount. We had been misled about the nature of the way, and we had misled ourselves. But we had managed at last to reach our pilgrimage destination—or at any rate, we had reached St Michael’s Mount.

Elyn Aviva is a transformational traveler, writer, and fiber artist who lives in Girona, Spain. She is co-author with her husband, Gary White, of “Powerful Places Guidebooks.” To learn more about her publications, go to www.powerfulplaces.com and www.pilgrimsprocess.com. To learn about Elyn’s fiber art, go to www.fiberalchemy.com. Gary’s blog about their expat life is www.fandangolife.com.