Embark on an adrenaline-filled adventure with Nancy King as she recounts her gripping tale of being lost while hiking solo at age 86 as she faces treacherous slopes, deep snow, and unforeseen obstacles. Discover how her resilience and unwavering spirit guided her through the toughest of trials, reminding us all of the indomitable power within ourselves. Share the triumph of finding her way back, and be inspired to tap into your inner strength.

All tagged New Mexico

Can you go home again?

Thomas Wolfe once said: “You can’t go home again.” Was he right? Carolyn Handler-Miller wouldn’t know until she tried. She was determined to find out.

Starstruck

This is the story of native New Yorker Cliff Simon, who goes to New Mexico and experiences, for the first time, the magic of the Milky Way in an entirely Steven Spielberg moment.

The “Goat Rope” Trip: Lessons Learned About Travel in the Time of Covid-19

Not every trip goes as planned, especially during a pandemic. But if the success of travel can be measured by human kindness or a newly acquired bit of local lexicon, then Laurie Gilberg Vander Velde’s brief attempt at travel during COVID-19 was a win.

Meow Wolf: Where Wonderment Compensates for a Lack of Words

Travel writer Fyllis Hockman was left speechless (well, almost) by a visit to Meow Wolf, an immersive art experience in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

On The Trail of Discovery in New Mexico: Hiking Tent Rocks

It's not always easy to age. But here's the thing. It happens to everyone. In this story, discover how writer Carolyn Handler Miller faces the physical and emotional challenges of aging during a hike at Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in northern New Mexico.

I learned long ago the correct way to hike the trail to Chimney Rock at Ghost Ranch in the Rockies of northern New Mexico. I knew I needed water, a jacket for rain, sunscreen (although in 1971, when I was six, we called it tanning lotion or sun block - and we only used it at the pool), and sensible, rugged shoes. Footwear absolutely needed to be ankle height, if not higher, with strong laces and a traction-optimized tread. Twisting an ankle always loomed as a real threat, and a good, solid lace-up boot would help prevent that. Snakebite, by a prairie rattler or the dreaded diamondback rattler, could not only wreck a vacation, it could take a life. As a child I had no choice in the matter. When we hiked Chimney Rock, I wore my Red Wing hiking boots, which were perfectly serviceable.

My love of cowboy boots came from my very first pair of Acme harness boots. I got them as a young boy in Nebraska, and they helped me feel independent, strong, protected, and stylish. I lost track of those boots, and really didn’t have another pair until late into high school, at which time I was too cool to wear them -- city kids just didn’t wear boots. We left ‘wearin’ shit kickers’ to the country boys. I chuckle when I return to Nebraska now, because with enough distance, I can see that my hometown has and probably had plenty of room for cowboy boots.

by Izaak Diggs

It would be easy to dismiss Barstow as a wasteland: You've got the heat in the summer and the poverty year round. Faded mobile homes and salvagers making monkey shapes as they strip valuable tiles off collapsing houses. To the casual glance it is just a place to fill your gas tank or grab a burger or use a restroom. Just another desert town, just another exit or two along the interstate to somewhere else. Why was I there? Was I following a genuine spark of inspiration or had I lost my mind? All I could do was wring my hands, question my sanity, and take more notes.

Barstow has always been a hub. Starting in the nineteenth century it served long distance travelers and the mining towns in the region. The desert is a popular place for mines: Men digging holes in the ground, getting a little closer to Hell in the hope of cheating the Devil at poker and getting a monopoly on brimstone. Gamblers with chin beards and suspenders who directed other men into the dark recesses of the earth. They oversaw the creation of towns that thrived for awhile only to die and be reclaimed by the desert after. Fortunes made and lost; a story told countless times in the history of mankind. The story of Barstow is nearly identical to scores of towns scattered like seeds throughout the Southwest.

I went down to the desert with nearly every penny I had. I stood on a salt flat, waited for the wind to rise, and tossed all the bills in the air. They were carried in every direction; to fast food restaurants and cheap motels and gas stations. Like those men with chin beards and suspenders I gambled everything I had on a dream, on an idea. I gambled it on the desert; I gambled it on all the little towns like Barstow and Lone Pine and Tuba, Arizona and Capitan, New Mexico. I rolled the dice that there was a story there lurking like a scorpion in a yucca.

The phone rang, a welcome break from correcting student essays. “Want to take a road trip to New Mexico?" asked my son. “I’ve got five days off and I haven’t seen you in a while.”

My son. The southwest. Five days of fun. "Of course," I replied.

The Magical Dunes of White Sands

words + photos by Jean Kepler Ross

They say one picture is worth a thousand words. I believe being there is worth a thousand pictures.

For several years, I edited a travel guide about New Mexico and saw many photos of the gorgeous white sand dunes in southern New Mexico, known as White Sands. Each photo illustrated the beauty of the dunes - sensuous mounds of sand, blooming yuccas, delicate lavender wildflowers, kids jumping off the dunes into space...it all intrigued me. I traveled in that area a few times but never had a chance to actually visit White Sands until a few weeks ago.

The Bosque Is For The Birds

words + photos by Laurie Gilberg Vander Velde

“Maybe I will go to the car and get my tripod,” I said to my husband. We were at the edge of a mostly frozen pond, standing on snowpack, bundled up against the 19 degree cold in the pre-dawn dark. A glimmer of light was starting to show in the sky. We had staked out a spot in the line of tripod-wielding photographers with their mega-humongous lenses We were all waiting for the awakening snow geese and sandhill cranes to perform their morning “fly out.” We were at Bosque del Apache, a National Wildlife Refuge near San Antonio, New Mexico about an hour south of Albuquerque. It’s a place known to many serious bird watchers who throng to the area in the winter to watch thousands and thousands -- and thousands of snow geese and sandhill cranes come and go.

We are not avid birders, nor am I a zealous photographer. How could I be? I love taking pictures and dabble in PhotoShop, but I tote a point-and-shoot camera. It’s top of the line and somewhat flexible, but it’s still a point-and-shoot, and the SLR crowd look at me with some disdain. Much as I would love to use a digital SLR and be able to change lenses, my body just can’t schlepp that much weight. And my husband, despite my batting my eyelids at him, has turned me down flat. It was hard not to be intimidated by the very serious looking phalanx of expensive equipment lined up on tripods waiting for “the moment.”

We are not avid birders, nor am I a zealous photographer. How could I be? I love taking pictures and dabble in PhotoShop, but I tote a point-and-shoot camera. It’s top of the line and somewhat flexible, but it’s still a point-and-shoot, and the SLR crowd look at me with some disdain. Much as I would love to use a digital SLR and be able to change lenses, my body just can’t schlepp that much weight. And my husband, despite my batting my eyelids at him, has turned me down flat. It was hard not to be intimidated by the very serious looking phalanx of expensive equipment lined up on tripods waiting for “the moment.”

Our home is now in Santa Fe, so we made the easy two plus hour drive to the Bosque (means “forest” in Spanish) the night before, aiming to get there in late afternoon in hopes of seeing the “fly in.” This is the time during the golden hour before the sun sets and the moments after sunset when tens of thousands of snow geese and sandhill cranes fly in. A foot of snow had closed the refuge a couple of days before, but the plows had sort of cleared the roads. The observation decks were still snow covered. The big problem was that there were limited areas of open, unfrozen water in the ponds, and the birds want to land on open water where they are safer from predators. The helpful folks at the visitors’ center can tell you where the birds landed the night before, but the birds don’t file a flight plan, so we can only guess where they might land tonight.

Traveling Back Through Time in Taos

Although Starr Interiors, the gallery that I’ve had for decades, has been housed in what was once the home of one of the founding artists of Taos, New Mexico, E.I. Couse, only recently have I gotten entranced with the history of the building. I’ve known about it, but it’s always been in the abstract. My deed was signed under the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, but the building which was originally constructed as a private home, existed long before that. I’d never given much thought to the previous owners and the part they played in the colorful history of Taos.

Since making a connection with Virginia Couse and her husband, Ernie Levitt, who have the Couse Foundation, I’ve become inspired to do some of my own research into this historic building. They’ve been good enough to provide us with some photos when Virginia’s grandfather and his wife, the first Virginia, lived in the house, from 1906-1909, calling it Las Golondrinas. It was there that her grandfather built his studio by opening up the roof and adding on what looked like a greenhouse to provide him with the northern light he needed to paint by.

He also often painted in the courtyard. This courtyard was beautiful then, as now, and a photograph caoturs Couse sitting in the doorway at his easel with a handsome young model from the Pueblo standing in front of him. In another, we see him sitting in the courtyard on one of the rocking chairs with his wife stretched out on the grass, hollyhocks and Virginia creepers lining the sides of the courtyard.

by Jim Terr

I had lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico for 23 years before it occurred to me to offer to move back to Las Vegas, New Mexico (the “original” Las Vegas!), 65 miles east, where I was raised, to help care for my mom, aged 92 at the time.

photo by jonnyphoto via flickr.comMy brother had been doing the honors (living with her, in her beautiful red-brick Victorian we were raised in) for a year, and I thought I’d offer to relieve him. My mom couldn’t believe my offer, recalling that a year earlier, when she had asked me if I’d like to move over there, I had responded “I’d rather slit my wrists.”

photo by jonnyphoto via flickr.comMy brother had been doing the honors (living with her, in her beautiful red-brick Victorian we were raised in) for a year, and I thought I’d offer to relieve him. My mom couldn’t believe my offer, recalling that a year earlier, when she had asked me if I’d like to move over there, I had responded “I’d rather slit my wrists.”

My suicidal reluctance had been due to my attitude that Santa Fe was fascinating, culturally alive, hip, filled with beautiful, interesting people and romantic prospects, whereas Las Vegas (population 15,000) was insular, uninteresting, provincial, stagnant.

As I was cleaning up to move out of the place I was living in, my ever-active songwriting mind was generating a beautiful tribute song about Las Vegas, my home town, perhaps as a coping mechanism, a reflection of my deeper excitement about moving back there despite my well-developed bad attitudes about the place.

Now, a little over six months since moving back to Las Vegas, I am able to see more clearly what a tremendous transition was involved in moving back – and in gradually overcoming the horrible attitudes I had developed about my dear little old home town.

by Eric Lucas

Hardly anything seems secret about a kernel of blue corn. It’s the size and shape of a baby’s tooth, the indigo color of ocean dusk, not rock-hard but sturdy, like old pine.

Such a seed would be a secret, were it a product of American industrial agriculture—patented, engineered at a molecular level, sold under some trade name like Blue 7X-RR. You would pay a large Midwestern company to have some; you’d use huge machines like science fiction robots to lay it in the ground; pour on it chemicals with carbon-chain formulas as long as Finnish words; autoclave it into foods as artificial as plastic. And you’d get your pants sued off if you attempted to replicate it or reproduce it in any way.

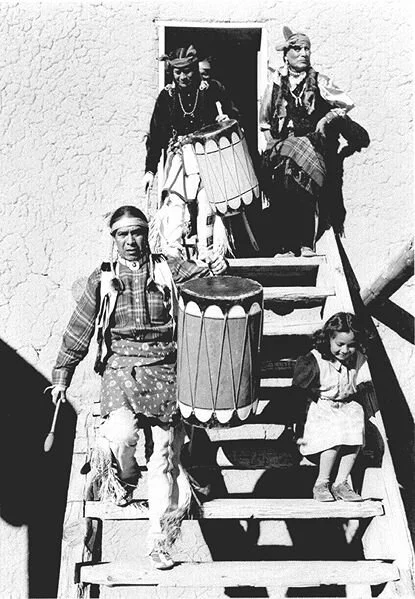

Photo by Manya Kaczkowski, 2010But the handful of blue corn seeds I’m holding represent a gift from, first of all, Robert Mirabal, a Taos Pueblo resident; also a gift from two millennia and the ground on which a billion people live. Corn is the bedrock of civilization in the Western Hemisphere. It built a dozen empires in Mexico and South America; helped create two dozen thriving cities in the desert Southwest about which Spanish explorers marveled so much that their colonizer, Don Juan de Oñate, declared his conquest a “kingdom.” Nuevo Mexico; it’s called New Mexico now, but still part of the kingdom of corn. And the seeds Mirabal has given me are no secret, just gifts from that kingdom’s treasure.

Photo by Manya Kaczkowski, 2010But the handful of blue corn seeds I’m holding represent a gift from, first of all, Robert Mirabal, a Taos Pueblo resident; also a gift from two millennia and the ground on which a billion people live. Corn is the bedrock of civilization in the Western Hemisphere. It built a dozen empires in Mexico and South America; helped create two dozen thriving cities in the desert Southwest about which Spanish explorers marveled so much that their colonizer, Don Juan de Oñate, declared his conquest a “kingdom.” Nuevo Mexico; it’s called New Mexico now, but still part of the kingdom of corn. And the seeds Mirabal has given me are no secret, just gifts from that kingdom’s treasure.

Discover the Exotic on a Road Trip

“None of your business,” she said. The short, curly, white hair bounced as she shook her head, but the brown eyes smiled in her beautiful, tanned and weathered face. Half Navajo, Suzie (not her real name) has lived in Rio Grand pueblos in New Mexico all her life. We were sitting in a rambling adobe house near the village where she lives with her husband. Grandchildren and daughters dropped in from time to time as we talked. The smell of cedarwood smoke curled around us, and tin-framed pictures of saints glinted on the walls.

The Sierra Club hike was advertised as: Strenuous Hike along the streams and meadows of the Grass Mountain area of the Pecos Wilderness, ~10 mile one-way hike with car shuttle, possible 2000 ft. cumulative climb.

In addition to nearsightedness and a deep sense of curiosity, my Dad and I shared a love of good stories. After his death two years ago, I had the opportunity to travel in his tire tracks. My road trip became a lesson in discovery, geographically and emotionally, showing me aspects of my father I had never seen and beautiful places I’d never visited. Ghosts have a creepy reputation, but my father’s made the perfect traveling companion.

Let’s start at the beginning. My Dad was Tony Hillerman. During his 35 years of writing best-selling mysteries, millions of fans treasured his stories of Navajo detectives solving crimes on the panoramic Navajo Nation. He also inspired me to start The Tony Hillerman Writers’ Conference, where he served as our most popular faculty member for several years.

Before Dad died in late October of 2008, my photographer husband Don Strel and I had launched our own book project, “Tony Hillerman’s Landscape: On the Road with Chee and Leaphorn” to show readers who had never been to Indian Country the settings in which the fictional Tribal Officers solved crimes. I gathered quotes from Dad’s books that described places where his detectives pause to comment on the scenery in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado. Then we hit the road for Baby Rocks, Teec Nos Pos, Toadlena, Church Rock, Kayenta, Tsaile, Tuba City and other breathtaking places Dad loved.

Don and I finished the book with both relief and regret a few months after Dad died. We decided to promote it and honor my father’s memory with talks and slideshows to support public libraries. Little did I know that I would be getting most of the benefit, priceless stories from people in the audience whom my Dad had touched: loyal readers, distant relatives, Indian consultants, long-lost friends, and former co-workers and students from his days at the University of New Mexico.

At the small Placitas, N.M. library, a woman came up to me after my talk. “I have to tell you how I stalked your father,” she said. I was all ears.

Because of a silver-colored horse named Concho and a notorious outlaw named Billy the Kid, my tether to the digital world got snapped. And, as it turned out, I was grateful. I’ll explain.

Because of a silver-colored horse named Concho and a notorious outlaw named Billy the Kid, my tether to the digital world got snapped. And, as it turned out, I was grateful. I’ll explain.

It all started about a year ago, when I heard about an intriguing trail riding vacation called the Tunstall Ride. It had a Billy the Kid theme and was based in southern New Mexico, major Kid territory. According to Beth MacQuigg, the ride manager, there would be three days of trail riding and we’d be traveling over some of the same rangeland that the Kid would have ridden over.

Riders would be housed in guest rooms on a private ranch adjacent to the property where the Kid once worked as a ranch hand. Known as the Tunstall Ranch, it was owned by his boss, Englishman John Henry Tunstall. Billy was riding with him one day when Tunstall was gunned down, was the first person to be murdered during the infamous Lincoln County War.

That bloody conflict aside, the land we’d be riding over was reputed to be some of the Kid’s favorite country. Beth told me that most people would be bringing their own horses, but for those of us who were horseless, like me, rental horses could be provided. As someone who loves horses, trail riding, and Western lore, the Tunstall Ride sounded immensely appealing, and I signed up. I signed my husband up, too. Though Terry doesn’t ride, he could hang out at the ranch and join us for meals and explore the historic sites with us that we’d be visiting without the horses.

Santa Fe to Tucson in a one-day mad dash

Jack the Pup is riding shotgun on the roommate’s lap as we head west on I-40 at nine AM, planning to reach my sister’s house in Tucson in time for dinner. The first miles across the desert, numbingly familiar by now, yield as this time we’d planned a back roads excursion south, just across the Arizona border. The map shows one of those intriguing dotted lines, a scenic highway, just what we need after hours of rumbling 18-wheelers…

To ready ourselves for adventure, we stop in Gallup at what is now our favorite eatery: Earl’s Family Restaurant. Here in Navajo Country Earl’s is shopping center, family reunion, and good staple New Mexico food: guacamole, burritos and so forth. Outside, Navajo craftspeople jam the sidewalk with their tables; inside, they patrol the aisles, silently holding out pins, bracelets, necklaces, and, in a departure from the usual, a pair of weird lamps, the ceramic bases coated with sand and then painted with iconic motifs. I’m charmed, I must buy at twenty dollars each, then wonder, too late, where in the world I’m going to put them….